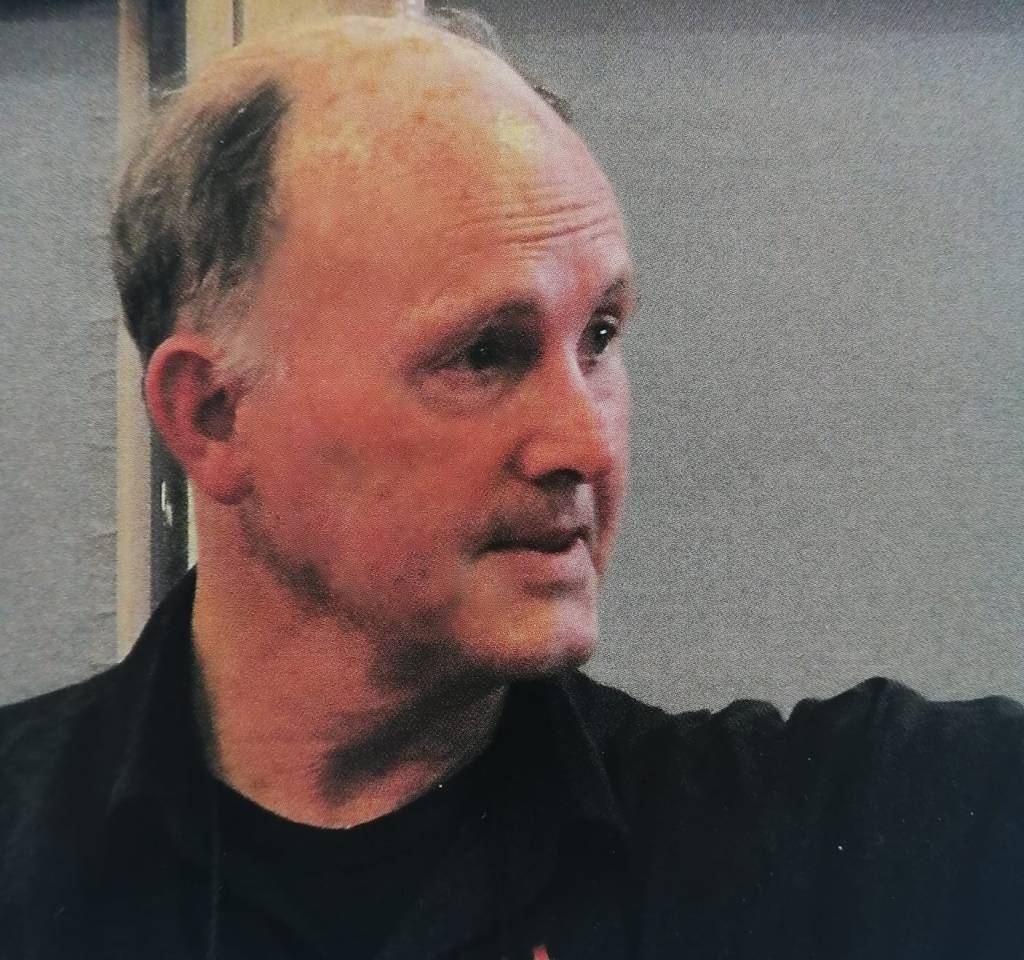

In memory and with gratitude for the life of

Julian Cooke

30 April – 24 February 2025

Julian Cooke was a member of our Poetry Group that met at my home. He had been a member of this group over a period of 20 years. The group started in Fish Hoek about 25 years ago, moved to a number of different homes, went online during Covid, and now meets at my home. A Fish Hoek group still functions and there is another group in Simon’s Town. Within the group Julian shared his insights on the poetry of other poets that had come before us, old and new, and had published a number of poetry books privately, amongst his family, friends and Church community. His most recent offering is called PEOPLE IN THE STREETS, and other poems 2024. He died recently and suddenly of cancer.

Who are these people in the streets to which the title refers? In their scaling down as a retired couple Julian and Judy went to live in a small sized apartment in the suburb of Kenilworth, Cape Town. Almost every morning Julian went walking through the streets of Kenilworth. On these journeys he met the down-and-out people who slept on the pavements, in shop shelters, wherever they could find a space. Street people who begged and found their food in the dustbins of the suburb.

There are those who fear these people, who are sometimes irritated by the mess that some of them cause, who would like to see them go.

Julian however, met them, stopped to talk to them, befriended them and honoured many of them and these meetings, in his poetry. They are the people of the streets. I see his journey through the streets, as a modern-day journey of Francis of Assisi, journeying through the market place of his town, honouring the humanity of every person he met.

In EARLY MORNING WALKING

I’m walking: many take their walk

like me before breakfast – we go

to wash our lungs with dawn’s quick air,

to dance the blood through the body.

The poem then looks at the reason why people go on these walks, some led by their dogs.

Then he meets Mzwandile, the watchman,

he walks from

miles away but he’s always there

before breakfast with shining boots

watching, when I am swinging by.

On Tuesday, refuse pick-up day,

ragged people jog along with

plastic bags or scramble pell-mell

with supermarket carts from bin

to bin, don’t balk one second to

to dip their bodies in and scratch

for some small prize to eat or sell.

In FREE LIKE LEAVES, while mezmerised by the beauty of autumn leaves falling, he looks beneath the tree and sees three cardboard boxes folded, he sees a balaclava sticking out of a box,

Yes, there is a man in there, all boxed

up for last night’s cold, but not boxed in,

he’s free like the leaves and tomorrow

may be whisked off almost anywhere.

In NEARLY FORGOTTEN he comes across what appears to be a corpse lying beside a channel beneath road level, a man who appears to be a painter from the items beside him.

Hey! Help! I beckon, gasping, to

a fellow walker up the way,

here’s a body look here! God, he

yells. We bend. A grunt! The body

grunted! How can he possibly be

alive? Hey! I say, you must rise

out of the gutter, giving him

a prod, he grunts and sighs.

All I can do is go away…

In his concern, Julian returns the next day to the find the gutter empty, and ponders. Perhaps he /sobered up and went off, laughs now / about his long hard night – or died,…

In NOTHING,NOTHING a street person asks him for money, but on this occasion, he has nothing to give:

Nothing? Nothing? Sorry, bhuti,

not today, I’m on my walk but

tomorrow maybe, sometimes I

do have something in my pocket

but find you lying crumpled up

against the door, your eyes like slits,

wired up to keep the sleep inside,

why you favour this piece of floor

as bed seems so strange, …

In FATHER SON, he walks down a lane and passes the sleeping place of Themba. His sleeping place under a tree, is shaded by a curtain hanging from the branches. Themba’s asleep, but as he makes some fifty paces past the spot, he hears:

Papa papa hurled from behind

and there he is a scarecrow or

a scraggy angel whirling down

the road in a ragged blanket

Julian, chuckling hands him the gift, Themba rocking murmurs, papa I’m sleep haayi he bless you/ Jesus Christ you papa papa.

Like Francis of Assisi, Julian stops on his walk and engages the people on the street. They in turn are moved by this recognition, and respond warmly and give something of themselves, their warm humanity, as seen is this short poem, NEIGHBOUR,

Each day I pass this man, he sweeps.

the pavement of a coffee house,

I pass, he sweeps, I pass, he sweeps,

for weeks, until one day I say

good morning, brother, every day

I pass you by and do not know

your name, mine’s Julian. He stops,

turns, unbends the wire of his frame,

dust off his hands, oh, thank you! Rough

his palm in mine, cheeks smiling high

and wide, eyes greet me, shining, spring.

flowers in my winter garden,

hello friend, they say, I’m Pardon.

In PRINCESS In the murk of dawn, he sees a silhouette of a woman, a princess, and as she comes closer he sees, a woman, bearing neither robe nor necklace / round her slender shoulders, rather / hanging to the ground, her blanket, / someone’s threadbare, cast-out bedspread… later we read: She crouches down, somewhat jerky / shifts aside the manhole cover / and works her bedding down inside.

In STREET FIGHT, two early morning pickers are out with their black bags, unpacking bins for their loot and are set upon by two other pickers. A knife is pulled in their argument, so the early two have to vacate the area, but as they go they threaten that they will not forget. A voice is heard from a house: snarling “don’t spread bloody mess there, / you pick up put back everything”. The irreconcilable irritations of those who possess and the dispossessed and the irony of “a person nearly died there”.

In ACCIDENTAL FRIENDS there are two walkers who pass each other often, and although Julian is eager to greet, the other on the other side of the road passes without any recognition of the poet. Julian wonders why? Is there a distrust of each other because of apartheid, removal to the Cape Flats, the hardships, race. But then,

By accident one sunny day

we stumble into each other

suddenly around a corner

so close so unexpectedly

we’re all a little embarrassed

I say hi there how’re you we swap

names at once our faces light up

like friendly stars and nowadays

we start waving at each other

when we’re at least three blocks apart

IN BOUND LEGS, he tells of seeing a man outside his gate sitting and binding his feet with rags he has found in the bins on the street. Old rags, dishcloths, sheeting, plastic bags bound about his feet like an old mummy. He reflects on how shoes keep body and soul together on the journey; how binding is tough on the feet, cuts to the skin. Then one day he sees him lying along his bed, under a culvert, his home, then

when I call out molo bhuti

he sits silent and I can see

he has no eyes nor mouth only

legs enshrined in rags wherein his

lone life unwinds

In the poem KHANYI’S BROTHER, he finds Khanyi, who is resting on a step of the restaurant where she works as the chef. They talk about their families, but today she is in mourning as her brother was shot and killed.

Shot shot in the head, they shot him

at the bank on his way to work,

at New Flats, Langa taxi rank;

they murdered him for nothing, took

money? no, purse? no, phone? nothing.

Next week we must take him back home,

for he must never lie alone,

home at Cofimvaba hill, home

where all his ancestors lie in

stony earth…

She feels the loneliness of her brother’s death so deeply for they are twins. She knew him in the womb and now she feels so alone in her world. Julian stands so helpless before her,

how can I a chance encounter

in the road do anything to

mend your grief your trembling, weeping?

Come daughter, let me comfort you,

Hold you safe and warm in my arms.

The poem WATCHMAN reveals the life and hardships of Philemon, the watchman of the block of flats where Julian lives. His is a twelve hour shift. Julian sees him early mornings when he is leaving for his home in Masiphumelele, some thirty kilometres away. Julian often sees him again when he returns to work for seven in the evening. His life is entirely dominated by work, eat sleep, dream travel. His life has recently changed for the better as his wife has come to join him from Zim, but his two daughters are still in Zim being looked after by a sister. The poem ends with a touch of humour, but even humour belies a touch of fear:

Who then watches over her snores?

I blurt; he smiles, she locks the door.

In the final poem of this section within the book he asks whether the people he meets, especially those who live on the street, feel free or feel fenced in? There is a sense of freedom of course, but most of us would choose not to live that kind of life. Most of us would choose our own burdens and a nice bed and home at night. Julian, the poet and Francis, the mystic remind us that life is about relationships with the other and with the whole of the natural world. Many people will treat people on the street as those to ignore, or fear or to view with disdain and mistrust. Julian engages those he meets on his walks, greets them politely, until they are prepared to respond. He shows us that every person matters and has to be treated with respect, with the awareness of their dignity and humanity.

My favourite poem of Julian’s walk through the suburb is RESURRECTION, which I read for you.

Close to where I live, just around

the corner up against a wire

fence one Sunday morning, I see

a wheeled refuse bin tipped over

and spilled behind, spread thin across

the tarmac pavement, a trail of

flotsam, a jacket inside out,

plastic mattress wrapping , bitten

polystyrene cups, flattened sheets

of cardboard, gin bottle. Poked out

two feet, two scarred feet on lean shins

toes spread rigid with lifelessness,

amputated like a painting;

the spill of debris’ far too thin

to shroud a human body, yet

now I see, tossed down in the clump

of discarded junk, a head too,

half-hidden in its ragged hair,

half a face – alive, asleep, eye

as jumpy as a dog dreaming

in the brilliant, early sunshine.

I peer down on him as he would

peer in bins every Tuesday

when the refuse truck grinds in here

and greedily skoffs its breakfast,

when suddenly the face turns up

the other cheek, imprinted with

tarmac gravel; skinny eyelids

slide open red insides, I say

“Hey, are you ok?” His split lips

and mouth of sticky teeth grin wide:

“Hey, madala, it’s the Lord’s day”.

He unfolds his paper body

and rises up beside his bin.

Should you want to discover more about the life of Julian Cooke, follow this link to The University of Cape Town’s tribute to him.

http://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2025-03-11-emeritus-professor-julian-cooke-19402025

DONATIONS TOWARDS MY BLOG MOST WELCOME